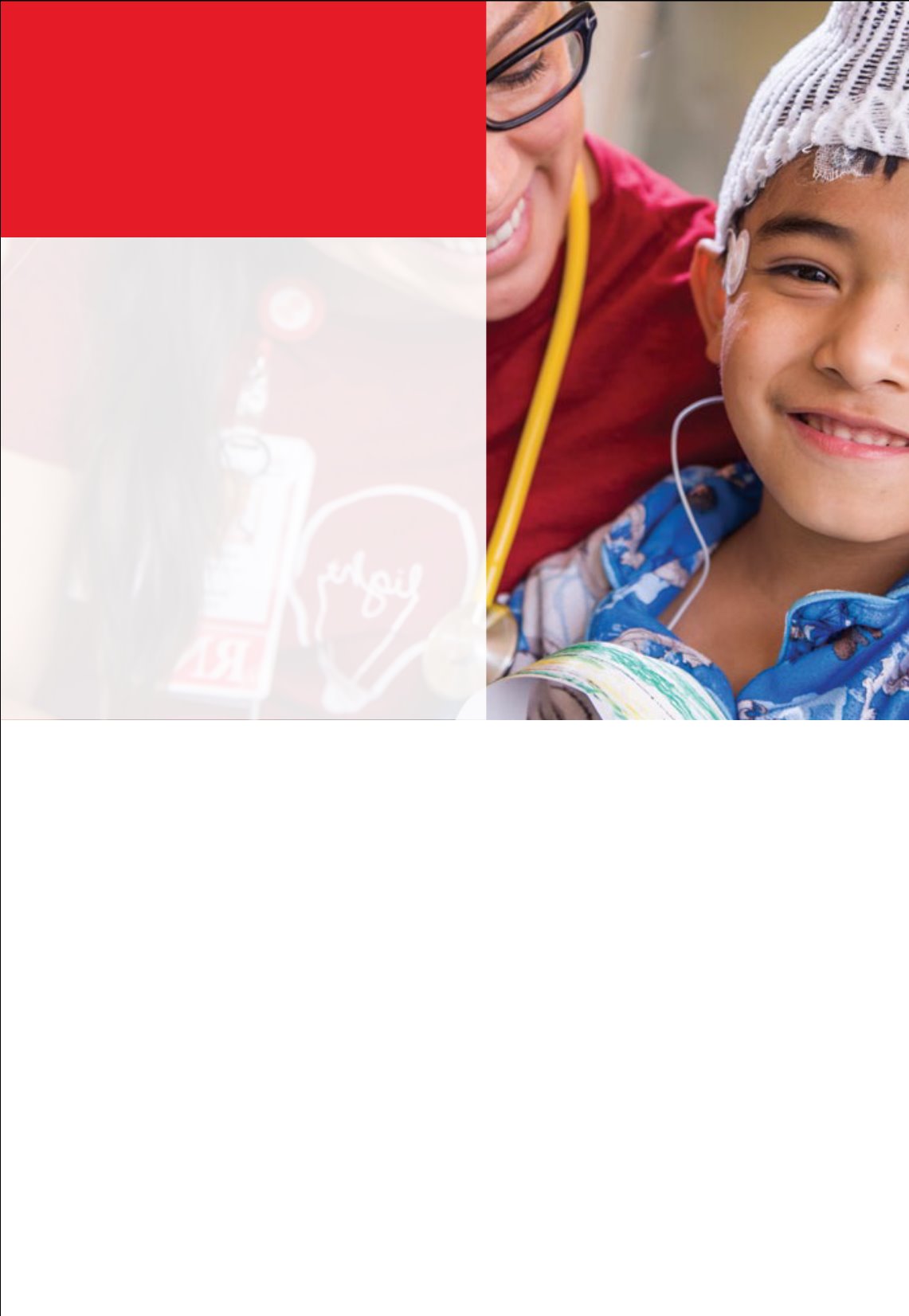

For young epilepsy patients at Texas Children’s Hospital, the process is part of

electroencephalogram (EEG) testing, which records the electrical activity of the brain to

monitor brain wave activity. The test often leaves patients’ skin red and irritated.

When Joellan Mullen, RN, CCRN, MSN, became a clinical specialist in Texas Children’s

neurosurgery unit in 2012, she found that at least 10 percent of the patients in the epilepsy

monitoring unit developed pressure sores because of their EEG electrodes.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), without treatment, these pressure

ulcers can cause cellulitis, an infection of the skin’s connective tissue. At its most extreme,

the ulcers can cause sepsis, which is life-threatening.

“Everyone just assumed we should expect pressure sores from this

type of procedure,” Mullen said. “Nurses would treat it afterward with

antibiotic ointment, but there was nothing being done to prevent it.”

Every month, some 30 to 40 children are admitted to Texas Children’s epilepsy monitoring

unit. Standard protocol called for technicians to thoroughly clean the children’s skin and

then attach electrodes to the forehead and scalp using surgical glue. As a final measure,

technicians wrapped the scalp with gauze and secured the gauze with surgical tape.

Changing

tactics,

changing

outcomes

Imagine undergoing a medical test that

involves having as many as 20 electrodes

attached to your forehead and scalp for days

at a time. The electrodes are held in place

with adhesive and then wrapped with gauze.

5 0

N U R S I N G O U T C O M E S

2 0 1 3

|

T E X A S C H I L D R E N ’ S H O S P I T A L